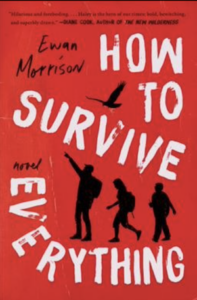

One of the questions I get asked often about my novel How To Survive Everything is: ‘How did you manage to write such a convincing teenage protagonist?’ It’s a lovely compliment. Sometimes it turns into: ‘why did you write a teenage protagonist?’ or the more pointed ‘what gives you the right to write a teenage protagonist?’ After all, I am a fifty-four-year-old man, and Haley Cooper Crowe is a fifteen-year-old girl. And she’s also abducted by her father, a man of my age. Creepy!

I struggle even to answer the simple ‘how’. I’m inexplicably superstitious when it comes to the art of writing and often sense that if I delve too deeply into questions of ‘how I write’, then my muse might feel betrayed and walk out on me.

There are some pointers, however, that I gave myself when writing Haley, and I hope that my muse will permit me to share them with you.

I too was a teenager

It’s an old cliché that we draw our fiction from the deep well of our own experiences, but I’ve always found it to be true. When I was writing Haley, I tried to recall what my main dilemmas had been when I was a teenager.

I realized that ‘the big issue’ of teenage life had been what Haley calls her ‘Hamletishness’. Her indecisiveness and procrastination; her sense that horrible grownups are pressuring her to make the things she fears most—‘decisions’. Even worse, ‘decisions for which she will be held accountable’.

As a teenager, I was utterly incapable of making any decisions and used to do that deeply annoying thing that became a trait of Haley’s—refusing to make any choice, so that an adult was forced to make the choice for me, and then blaming that adult for the outcome when it all went wrong.

So I gave Haley this character flaw, and it fitted well with her circumstances, in that Haley is a child of divorce with two diametrically opposed parents. One who is a city dwelling, career orientated single mother—Justine; and the other, her ‘deeply divorced’ father—Ed, who has become a secret Doomsday Prepper. When Ed kidnaps Haley and her little brother (to save them from the ‘end of the world’), Haley is caught in a tug of war between both parents and their opposing world views. In this situation, her ‘Hamletish’ inability to choose whose side she’s on becomes the dramatic tension in the plot. ‘Who should I trust?’ she asks ‘and who should I betray?’

This leads to some fairly tragi-comic disasters.

A teenager for teenagers?

In writing, I became enmeshed in the ‘Haley-voice’, as she speaks in a very direct first person voice, talking to us. Then suddenly, I thought, ‘wait, have I written a YA novel by accident?’

So I showed the story to a YA author friend. She said, ‘Nope, this really isn’t YA, because your heroine is so deeply flawed and neurotic – if this was YA she’d have to be decisive and invincible.’ She explained that YA heroes are really a fantasy of how teenagers would like to see themselves, rather than how teenagers really are (with shyness, changing bodies, neuroses, etc.).

So I showed the story to a YA author friend. She said, ‘Nope, this really isn’t YA, because your heroine is so deeply flawed and neurotic – if this was YA she’d have to be decisive and invincible.’ She explained that YA heroes are really a fantasy of how teenagers would like to see themselves, rather than how teenagers really are (with shyness, changing bodies, neuroses, etc.).

Now while this invincible trait is true of The Hunger Games dystopian genre, it’s not true of the conflicted teen protagonists in say—John Green novels, but he’s the exception to the rule.

I realized I couldn’t bring myself to turn Haley into a super-decisive action hero, so really, I was writing for adults about a teenager’s life.

If teenagers—since they are so often so much smarter than we give them credit for—wanted to read up in years, then that was fine by me. It would have to be, because having deeply flawed protagonists who drive us nuts with their mistakes is the only kind of character that I feel compelled to write.

Philosophize on the hypocrisies of adults

The most important thing I recall from my own teenage life was this sense that the world was like a Rubick’s cube. That ‘leave me alone’ thing that teenagers do is really ‘leave me alone. I’m busy trying to figure out how humans, love, philosophy, the universe, and everything really works.’

So I gave myself license to make Haley philosophical. I realized there’s a great tradition of teenage outsiders and anti-heroes (Catcher in the Rye, Mosquito Coast, How I live Now) in which introspective teenagers observe the ‘hypocrisies of adults’. They also work out that most adults don’t have the big philosophical answer at all, they’re just bluffing it. They’re ‘phoneys’ as Holden Caulfield would say.

Plus, I recalled from teenage life that I used to get these flashes of massive insight about life and the universe, and then they’d just fizzle out and remain beyond reach. Frustrating. So philosophical teenage sentences would come to a sudden halt with a ‘…but I dunno’ or ‘…or whatevs’.

These became essential Haley-ish things.

Cringe lingo

My own teenage kids fascinated me with their Generation Z jargon and slang. There’s fam, drip, patched, glow-up, pressed and sus and I was always a good year behind in my attempts to sound up-to-date.

‘That’s not what patched means, Dad!’ (Roll of their eyes.)

As an author, this posed a problem because if I was to try to make Haley’s lingo hip (wait is hip an uncool word? Is uncool also uncool?), then I’d be in a race against time, since with the publishing cycle a book can take two years to reach the shelves. Given that teenagers evolve lingo at such exponential speed, my book could have massively out-dated Gen Z jargon by the time it was published, and that would be ‘cringe’, as my kids would say.

As an author, this posed a problem because if I was to try to make Haley’s lingo hip (wait is hip an uncool word? Is uncool also uncool?), then I’d be in a race against time, since with the publishing cycle a book can take two years to reach the shelves. Given that teenagers evolve lingo at such exponential speed, my book could have massively out-dated Gen Z jargon by the time it was published, and that would be ‘cringe’, as my kids would say.

I could have just decided to cut all GenZ jargon out, but this would have made Haley feel less real. I, for one, as a teenager used to love the race to catch up with the trendiest slang. It’s a secret code, intended to keep adults locked out. There are also endearing remnants of the made-up words of the childhood-gang phase in it.

So I had to evolve a kind of Haley-speak that had odd and inventive re-uses of words that weren’t too ‘try hard’ and wouldn’t date, but that had evolved from her family life. So every eccentric word choice of hers would have a micro-history behind it: there’s vaventure, frick, blimp, and her excessive use of the words ‘actual’ and ‘something’. She also adds ‘ish’ to many words.

Haley often complains to her parents that they’re not understanding her or that words mean opposite things for both of them. So in making language a meta-battle in the story, I got to play with an invented hybrid teen-speak and also express some of that teen-angst over the ‘no-one understand me!’ emotion.

Haley also has to learn new lingo when she’s forced to live with the family of survivalists in enforced lockdown in the wilderness safe house. She has to learn the ‘Lima Tango Foxtrot’ lingo of walkie-talkies and the jargon of weapons—’so you ‘cock’ this crossbow, for real?’

Language, like love, is a battlefield.

Play against stereotypes

Stereotypes always make for lame fiction. I recall a particularly obnoxious sexist joke from As Good as it Gets: ‘How do you write a woman? You remove reason and accountability’. There are other clichés floating around the portrayal of teenagers and teenager girls. A knee-jerk tendency to portray them as ‘overly emotional’.

I decided to play directly against this with Haley.

I recalled from my own troubled teenage life that I used to zone out whenever situations at home or at school became ‘too emotional’. In later years, I discovered this was a psychological phenomenon called ‘dissociation’. I thought I’d give this trait to Haley, given that her situation was so extreme–being abducted by a survivalist father who believes the world is ending—after all.

So, in the book she says, ‘my parents had a truly terrible textbook divorce. I gave up trying to fix it when I was ten and gave up on all emotion by the time I was eleven. I’m so over saying ‘I’m so over this.’’

I realized that Haley had a quality beyond her ‘Hamletishness’ which was ‘analysis paralysis.’ When confronted by fraught, urgent situations, rather than taking action, she’ll go into hyper-analysis mode, dissociate, or even just pass out, rather than do the worst thing of all, which is ‘feeling emotion.’

To my surprise, I discovered that Haley really didn’t want to be in the drama of the novel at all, and that became darkly funny – to have a protagonist who is disgusted by the plot she’s trapped in. Sarcastic, ironic, refusing to take part; a teenager who doesn’t want to be in the world of what Gen Z call ‘adulting’.

That was where the final piece of the puzzle about Haley came in. I decided that Haley should write her own abduction diary as ‘How to Survive’ guide, and that became the ironic form that the book takes. And so it begins with what would become Haley’s typical darkly dry humor:

‘I’m still alive and if you’re reading this, that means you’re still alive too. That’s something.’