From Criminal Lawyer to Criminal Writer

By: Nadine Matheson

I can always hear Jesse Pinkman from Breaking Bad in my head whenever someone asks me what I do for a living. ” You don’t want a criminal lawyer. You want a “criminal lawyer.” It makes me laugh but I can read the looks that spreads across the faces of the people who always ask me the question. Those who have no idea about the true realities of criminal law inevitably are of the opinion that we spend our days thinking of creative ways to get our always, in their eyes, guilty client out of their criminal charges. It’s only when those asking the questions find themselves needing a lawyer that their opinion of a ‘guilty person’ changes, but that’s a story for another day. I’ve worked in criminal law for almost twenty years and have spent tens of thousands of hours in police station interviews and court rooms and almost every time that I’ve sat down with a new client, opened a case file, or read the transcript of a police interview, I’ve thought to myself ‘this would make a good story.’ It may not necessarily be the entire case that would make a good story, but a unique feature of a client’s personality. For example: my client pretending to be mute for 18 months. And that’s how it started, the birth of my transition from Criminal Lawyer to Criminal Writer.

I’m not the first and I definitely won’t be the last lawyer who picks up the pen and begins to write a mystery or thriller. The lawyers who immediately spring to mind who turned their hands successfully to writing novels are obviously John Grisham, Scott Turrow and David Baldacci. I was an inquisitive teenager in the early 90’s when I first discovered both Grisham, Baldacci and Turrow. At an early age I had my own lofty ambitions of becoming a lawyer, clearly influenced by the glossy world of LA Law and the more archaic but recognisable English world of Rumpole of the Bailey and Kavanagh QC. Obviously, the world that John Grisham’s lawyers inhabited—law firms working on behalf of the mob, law students uncovering government conspiracies—was nothing like the world that I inhabited, but I was transfixed by what I read and what I saw when the movie versions hit the big screen. Although I knew that I’d always wanted to be a lawyer and that one way or another I would one day be walking the hallowed halls of a court building and advocating passionately for a jury to acquit my client, I also knew that I wanted to write. Books and storytelling were always my first love, and I think that instinctively every criminal lawyer who finally sat down to write a book knew that they were helping to craft a story when they took on a new client and their case.

I could clearly remember sitting at my desk working on my client’s defence statement and saying out loud ‘this is nothing more than a story.’ I didn’t say that because I thought that my client was telling a pack of lies; what I believe personally has nothing to do with how I choose to advise a client or how I tactically prepare a case, but it was because I realised that part of my clients’ success will be down to how I present his story.

Years ago, I read an article that stated that very few British lawyers made it as crime fiction novelists. The article authors’ thesis was that British lawyers were unable to transition successfully to the publishing world and write credible crime fiction because we did not know how to tell a story, used complex ‘lawyer speak’ (their term not mine) and that we did not know how to write dialogue. I found the dialogue point extremely perplexing because Criminal lawyers are consumed by dialogue. We’re always analysing what people say in their witness statements, when giving evidence and when they’re being interviewed by the police. Most importantly a criminal lawyers’ ability to break down a complex case and deliver a persuasive and cohesive and succinct closing speech to a jury is ‘I would submit’ storytelling at its best.

As Criminal lawyers we are presented with a story, in my case as a defence lawyer, from the prosecutor. We open the case file and the first thing we look for is the elevator pitch—in other words, the particulars of the offence on the indictment sheet. So let’s say in my hypothetical story the defendant has murdered his business partner after discovering that he had stolen millions from their business and that he was in debt to a drug dealer. Now that I’ve been drawn in by the pitch, I have to establish my cast of characters i.e. the defendant, the victim, witnesses etc. So far, this story is looking pretty good and I may initially think that the prosecution has an open and shut case. As defence lawyers, we’re always looking for holes in the prosecution case, which in a story would be the obstacles that our protagonist would encounter. In this case, my client’s own version of events – his defence – is the obstacle in the prosecutor’s case and we as lawyers then start looking for holes in the prosecutor’s case and it is these holes that we use to build our own case. As criminal lawyers we start building our case by looking for evidence to support our client’s story, we look for more characters i.e. witnesses, and we think about their stories, what do they know, what did they see, and will there be a twist in the case i.e. the revelation of a smoking gun or the appearance of the real killer that will provide a riveting conclusion to our story and result in the acquittal of our client.

You can now see why it’s so easy for so many lawyers become writers. There’s the practical side as we spend hours drafting legal arguments or briefs (in the UK a brief is a document of instructions) or jury speeches, which means that we’re more than equipped to spend hours at our desks writing a novel. Our legal training has prepared us to pay attention to detail, to ignore as I call it the ‘noise’ or irrelevant material when we’re combing through pages of research. We’ve been trained not only to become advocates and experts in the law but also storytellers as we build our fictional worlds that we hope are equally authentic, compelling and persuasive.

I suppose that it was inevitable that I would be joining the ever-growing slate of lawyers who have become writers. It’s been fascinating to see the work of lawyers such as Wanda M.Morris, Imrhan Mahmood and Steve Cavanagh making their way in the publishing world but also equally fascinating to see exactly how we have used our legal skills and our experience as writers. An interesting observation that I’ve made is that US lawyers have been more likely to write legal thrillers whereas their British equivalent have tended to write thrillers, police procedurals (as in my case) or a legal thriller that is either set in the US or is taken from the defendant’s point of view. I have wondered if our ‘preference’ to write non-legal thrillers has something to do with the fact that we’ve subconsciously accepted that the legal thrillers were a US domain because we were almost drowning in US based legal thrillers, both in books and on the screen, back in the 90’s through the early 2000’s.

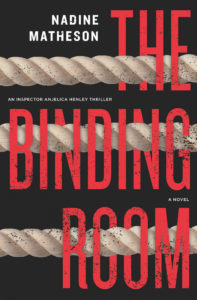

It’s been 18 months since my first crime fiction novel, The Jigsaw Man, a police-procedural was published and the second book in the series, The Binding Room will be published this summer. As inevitable as it was that I would be another Criminal Lawyer who is now a Criminal Writer, I feel that it won’t be long before I write my own legal thriller. I’m not sure if today’s criminal writers, who are ex or still-practicing lawyers, will ever hit the dizzying heights of commercial success that Grisham, Baldacci and Turrow achieved back in the 90’s but it’s a nice goal.