Interview with Erica Obey

by Anna Shura

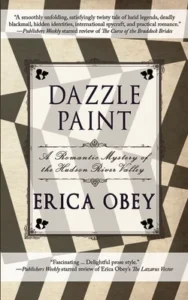

Erica Obey is the author of six books: The Wunderkammer of Lady Charlotte Guest, Back to the Garden, The Lazarus Vector, The Curse of the Braddock Brides, The Horseman’s Word, and most recently, Dazzle Paint. In our interview, Obey provided details about how she builds historical backgrounds and shares her most recent topic of interest: English country dancing.

Erica Obey currently resides in the Byrdcliffe colony in historic Woodstock, New York. She describes how she loves learning about her community and exploring its diverse past. Her latest novel, Dazzle Paint, is “probably the most personal” to Obey as it is set in the Hudson Valley in Woodstock. The name sake of the book, however, is from a different time and place, and Obey describes the metaphorical qualities of the title.

In our interview, Erica Obey describes a thorough background of how she constructs a novel. She discusses a multitude of research experiences, from pouring over materials in the National Library of Wales to YouTube spirals of English country dancing. She also acknowledges how her writing process begins with her character’s conversations and ends in a debate over eye color. Finally, Erica Obey offers personal insight on the rising genre of “cozies”, and shares “the standard definition of a cozy is, some dies, no one gets hurt.”

AS: Could you tell us about your latest novel?

EO: It’s a historical novel set in the Hudson Valley in Woodstock, where I live. It’s called Dazzle Paint. This is my third historical Hudson Valley novel. It’s probably the most personal to me, because I’m going to scroll back and give a little bit of Woodstock history. Woodstock was actually a very conservative little farming town until the artists came here in 1903 and formed a utopian colony called Byrdcliffe. Everybody thinks Bob Dylan and stuff; these were hippies 50 years before that. There’s a lot to be said about them. But anyway, I live in the Byrdcliffe colony full time now, which is very nice. So this is very personal to me, because this is really about my home. And we’ve been looking for a house in Hudson Valley for a long, long time. And we came here. We’ve never even heard of arts and crafts or anything like that. We saw the place, and we bought the house the same day. We just knew this was the right place for us. I can scroll back and give you a little more detail on arts and crafts.

I know I’m throwing a lot of things around here, but arts and crafts is sort of the movement that starts with William Morris Ruskin. This reaction to the Industrial Revolution, where the emphasis is useful not beautiful. One of the things it is, is a reaction against sort of the Victorian excess of stuffed birds and stuff like that. It’s also an emphasis on hand crafting. People up here would be like pressing their own mead, and Dan Morris dancing on the lawn, they did the whole thing. There’s obviously a nostalgia for something that never was. There is this whole idea that, you know, we’re going to get back to jolly old England when everybody was a weaver. So there isn’t a style yet.

The first thing you have to say about Byrdcliffe is it’s a utopian artists’ colony where we’re all building our own houses with our own hands and practicing art and printing and bookbinding. But it’s got servant’s wings, and you just get used to that. Dave Whitehead, who founded it, founded on the basis of Manchester steel [money]. He’s sort of Oxford and all that. He comes over here with his second wife, Jane, in Philadelphia. So there’s this incredible industrial fortune that is fueling all of this. What I find interesting about them, one thing I was really trying to capture, is all the people who came here met at Hull House in Chicago, which was Jane Addams Settlement School. Again, they are trying to teach young tenement children, get them out of the tenements, get them out of the workshops. They do tend to teach them staples and stuff like that. But they’re getting them out in the fresh air and trying to teach them about beauty and grace. It’s a wonderful kind of idea. One thing that I was always trying to capture is, even somebody like Jane Addams, they are so bound in their own conceptions that there are things they don’t see. They just don’t possibly see. And I was sort of trying to capture that in a nice way. They did an awful lot of good, but there’s also this point where they just can’t see past certain assumptions, including servants’ wings, so I was trying to capture that.

The three people who founded Byrdcliffe were Ralph Whitehead, Bolton Brown, and Hervey White. Nobody’s heard Hervey White anymore, but in the day, Theodore Dreiser thought his autobiographical novel was the great American novel. …He decided a rich man and a poor man cannot be friends. And he went and found his own colony across Woodstock called the Maverick. That’s the one where the real wild Woodstock stuff happened. So that was sort of what I was trying to capture here.

I can explain a little bit about the title. I’m sort of a postmodernist, I can’t help it. If you’ve never went to Yale, there’s no way to kick it out post modernism there. But one thing, there is a fantastic edge to this; there is stuff that’s happening on the edge between. The fantastic, something like the turn of the screw, where it could be a completely psychological explanation, or it could be a magical explanation. And I very much am interested in that. Dazzle Paint was a form of camouflage that was used for ships, especially in World War One and World War Two; it’s absolutely beautiful. The whole notion was with camouflage. With like a canoe, you can disguise it as a log or a tree or something, but you cannot do this with the ship. They tried. The thing was so top heavy, it never made it out of the harbor. So the notion of Dazzle Paint, is that you’re looking at a ship, you know exactly what you’re looking at, but you can’t figure out what you’re seeing. It’s got all these jagged lines and things so that you can’t tell where the hull is, how fast it’s going, how big it is. And I find that a perfect metaphor for literature, as well as magic, right? Literature in particular you know what you’re looking at, but you can’t quite tell. So I was very fascinated with that.

AS: I really like that. That’s a very cool background. I’m familiar with dazzle paint from the ship perspective, but I see it in that metaphorical way. That’s really exciting. I’m glad you’ve already kind of brought up how you write historically. What’s your research process behind that? How do you go about combining historical things into your writing goals?

EO: Well, somebody else coined this phrase, and it’s brilliant. So I’m sharing it, “The danger with historical fiction is, I’ve done all this research, and now you’re going to pay.” You know, I’m a research junkie, I’m a PhD. I’m not really that interested in theory. What I love doing is going through archives. I went to the National Library of Wales for my dissertation, The Wunderkammer of Lady Charlotte Guest. And I also did a paper on Anna Bray, who’s a folklorist in Dartmoor. And, like, there are two locks of hair in her archive. And this stuff, you just love touching it, being part of it. You either love this or you hate it. It’s one or the other, and I love it. So, it’s very easy for me to sort of follow my nose and just see what’s there. The danger is, very much this notion, you’re going to know everything. The information dump, as we call it, in mystery writing. You’re going to know everything I’m telling you about here.

We have a wonderful Historical Society here in Woodstock, and they are thanked on my acknowledgement page. I can’t thank them too much. I did go in there and go through their archives. I also hired a fact checker at the very end because Woodstock is a town, very, very deep roots. I mean, I’ve been here 20 years, and they’re like, “yeah, we sort of know who you are now.” But there are families here that go back 200-300 years, and I lived in terror of one of these families going “Oh, no, no, no, no, no, that wasn’t there.” I had a lot of things wrong. I can remember was I was having people happily drinking Sherry on Meads Mountain House, and I was like, “I should really check if they served alcohol up there.” I found one of their cards, and it was like, “it’s run on a temperance line.” So, that’s fun. It’s delightful. I suppose I could say something-now I’m treating you like a student-but one of the most wonderful things in the Historical Society was a social studies teacher from like the 60s and 70s that made her Social Studies class, I think it was probably a 10th grade class, do a written report of oral history interviewing people on these mountain houses. And they still have these reports. One was typed, and one was written in the most beautiful penmanship. What a fantastic research assignment for a teacher. A gift and what a fantastic resource that somebody thought to preserve this here. I used a lot of information from that. There was great stuff there.

AS: Wow, that is very interesting. I’m a museum junkie myself. What’s your favorite archive that you visited or what’s your favorite place that you’ve been to?

EO: I suppose I’d have to say the National Library of Wales because it was in Aberystwyth, and Aberystwyth is this town completely out of time and Wales. It’s like one of those old seashore towns still has a funicular leading up to a camera obscura. At five o’clock, everybody goes out on the boardwalk and needs their Cornish pasties and then goes home and watches the telly. So it’s this magical omphalos. I used to go there, take the mile long walk up to the library. There was a sheep field on the way; I never got to pat a sheep. I kept trying and trying and trying and never caught one. I’d work all day there, walk back down and get my Cornish pasty. And then, go back to the B&B. It was just sort of lovely and peaceful.

What was really fun, was I had a week, and my husband was going to join me. We were going to go hiking up in the mountains, Snowden and those. And so by Friday, I had gotten through everything. I went to the librarian, and there was something called a black box, black metal box. And I said, “I haven’t seen that yet. May I see it?” And he was like, “a new American.” He’s like, “I don’t really think there’s anything there.” And I sort of went on, you know, “I come all the way from America. Could I just see it?” He brought it up. He takes the lid off and it all but exploded with papers that were handwritten translations Lady Charlotte had done, something Willie Morris did later, Akun and Amiss, a medieval poem. There was all kinds of stuff in there. And now I had about 15 hours, including my husband, who’s very good natured guy and will take pictures of things. This was a little before cell phones with cameras at that point. But I get to get all this stuff recorded in like the space of 15 hours, but we did it. It was a lovely time. So I guess that’s my favorite. Woodstock Historical Society is pretty darn good, too. I’m a big supporter of them.

AS: That sounds amazing. I’ve noticed you’ve gone through several different historical time periods. Do you have any specific rationale behind choosing ones is it just a matter of interest at the time for which one you choose to write about?

EO: I would say my wheelhouse in terms of historical times, because I live here and I’m immersed in it, is probably about 1880 or 90, to about 1920. That’s sort of my wheelhouse. And Lady Charlotte and Anna Bray, they were actually on that cusp of romantic; they’re called late romantics, 1830s and 40s. But there was a very similar impulse. As a matter of fact, a lot of people who call pre-Raphaelites and the arts and crafts people of late romantics, there’s that same romantic impulse to find the poetry of the common man to better the common man and a find published poetry by a serving woman. That’s a story in and of itself. But it is that notion of finding folklore and the language of the people, which I know gets very, very twisted very quickly. Those are sort of my wheelhouse is when I wrote the Horseman’s Word.

I was like, well, what’s going on in 1880? I wanted to do this Irish thing, and somewhere I came across the draft riots in 1865, which are just horrific. There’s nothing good, you can say about them. And I was like, “Oh, my God, no, I don’t want to write about that.” And then you stop and think, “You have to write about that. That’s worth writing about there.” So 1865 is a little out of sort of what I call my wheelhouse.

Again, the scholarly stuff I’ve tended to do has been before 1840. The fiction, I think, because it’s set here in the Hudson Valley, for the most part, 1880 to 1928, there’s a lot of stuff still here that you can see. It’s very nice to be able to go to a place and look at things. New York City before 1840 that’s the Wild West practically. So I think it’s probably part of the convenience of the whole thing. You do sort of start getting lost in information. It layers on you. …When I was doing 1865, I wanted to have someone blow things up with dynamite, and you know, that little voice that goes, maybe you should just check [about dynamite]. I missed it by two years; you can have dynamite in 1867.

AS: That makes sense. How do you adjust your writing to be from a character and specific time period? Is there any specific research you do to make sure you’re in the right voice of a character back then?

EO: I tend to hear the characters before I see them. Regency novels can often be very, very guilty of this, of using every last little bit of slang, you’ve looked up. And it gets in your way a little bit. I wouldn’t want to compare myself to Dickens, but you know, they always said you could hear him just talking in the voices. He’d do the police in different voices. I think I’m a little bit lucky that voice is how I usually get into the characters and then secondarily setting. I always have a hard time going do they have green eyes or blue eyes? I never can quite decide.

AS: That’s interesting. I feel like a lot of authors are somewhat the opposite, where you could visualize someone before you kind of piece together their voice. So, is that is the voice your first step and coming up with the character? You just kind of hear them and then go from there?

EO: Yeah, I think it’s a conversation actually. I hear conversations and lines. You know, if you’re hearing the voices in your head, you might as well make them make a living for you or something up. But yes, I think I start with conversations. I’m getting a little ahead of myself here. I’m working now on a contemporary series about a female programmer and a AI program that she has programmed to write murder mysteries, which is very big these days. He (the AI) thinks he’s a great detective. So, I’m of course hearing all these murder mysteries.

The one I’m working on right now is about English country dancing. It all started with a big, bruising male character who has hidden depths when I imagined him being an unwilling expert in English country dancing. I started envisioned the car ride home after he has demonstrated these depths of him going, “I told you I went to West Point” and she says, “I thought you said you played football.” That’s actually where the entire series came from. That particular conversation; I can’t get it out of my head. I’m spending a lot of time looking up country dancing right now. And watching insane YouTube videos of country dancing, loads of fun.

AS: Wow, so have you discovered anything particularly fun about country dancing? What’s the wildest thing so far?

EO: The names. You go with the language, and they have titles like, Duke Stand and Barnacle Huggy. These people take this very, very seriously. I just like watching the videos. I went twice to the English country dance society here. I’m too klutzy. I just like watching them on YouTube. But it’s the language, and you look up some of these moves. There’s a whole code like the basketball swing; that one, its form is SCCS, which is step and set, cross cross step and set. It’s like a codebook reading these things. So yeah, I guess it comes to language again, you’re hearing that language and loving it, right?

AS: Yeah, I definitely would not have known about that. Okay, well taking a slightly different route here. In talking about classic mysteries, I noticed in The Lazarus Vector no one dies in the plot, and that’s a bit of a divergence from the classic mystery trope. How did that choice originate, and how did that change your writing of the story?

EO: I didn’t want to kill the kid. It’s an interesting because I am sort of moving more into cozies. The standard definition of cozy is, someone dies, no one gets hurt. Somebody had just written to me about a story they were working on about a young girl getting kidnapped, and that’s dangerous. You don’t want to go to those places. You want to kill somebody that you’re basically happy seeing die. That’s part of the reason why in Dazzle Paint. I put these girls off into the fairy realm because there you can do a lot more than in real life. I was Peaching at Fordham at the time, and I’d go by this church every day on the bus. I would look at it and just go, “a miracle needs to have occurred that church.” Then I tried to come up with the miracle. Actually, I’m such a coward that when I originally wrote the book, I made sure you knew that kid was all right in chapter one, and my editor was like, “you have got to be more statistic Erica.” So you don’t find out he’s okay for a little while after that.

The thing about a cozy is, and I am moving toward them at the moment, I think everybody in the pandemic right now wants to go to this safe place. It’s probably not a coincidence, that fantasy and cozies were very, very popular in their heyday, right in the 20s and the 30s. Same kind of thing. Where you just don’t understand the world anymore, and you go back to the safe place where order is restored. Everything’s nice, and it isn’t so bad that person died.

AS: Yeah, I could see potentially a resurgence of that sort of style coming into existence because of all the pandemic happenings. Do you think that’s something that’s going to continue to grow because of this?

EO: I hope so. I think cozies are sort of hot, and incidentally, that’s a very iffy word ‘cozy’, some people hate it. Some people love it. Some examples of cozies might be The Stranger Diaries by Elly Griffiths and The Thursday Murder Clubs by Richard Osman. Not so much Anthony Horwitz, but I’m not getting in any fights. These guys are all playing with the postmodernist idea of a detective story being a story about reading and writing. The Topology of Detective Fiction, is a book where the author is pointing out that really, the reader and detective are together allied against the criminal and the writer. There is an intellectual game about reading and construing meaning out of snippets of information. I think the authors I like the most right now would be Allie Griffiths and Richard Osman. I swear Anthony Horowitz does this to where they are very much playing with this notion of a text. There’s always a murder text, and an actual investigation. But this is about mystery writing as much as anything else. So those are some of my favorites. I mean, more conventional cozies there’s malice domestic. That’s a big conference. There is a very strong resurgence for a lot of them.

AS: Who are your top authors that you enjoy? And what’s next on your reading list?

EO: Well, I’m judging the contest right now, so what’s next on my reading list is what’s coming across the door. I’m reading a lot of the old-fashioned mysteries right now. Mary Roberts Reinhart I’m trying to read my way through them. John Dixon I like an awful lot in terms of what I’m reading for myself. In terms of contemporary writers doing things that I’m interested in, there’s a series called Bryant and May. I like it a lot. They do tend to be English more than American. Richard Osmond, English and so is Anthony Horowitz. Maybe I like that snarky British edge. I beyond that, for pleasure reading. I am just trying to go through some of the more obscure old ones. There’s a wonderful blog called “In the Search of the Classic Mystery Novel”. I just tried to pick up whatever he’s brought. That’s my fun reading, for the most part.

AS: Excellent. Well, here at The Strand, we’re also a fan of some snarky British humor as some of the original Sherlock Holmes publishers. Sherlock classically wears his deerstalker, but I’m curious, what would be your defining detective accessory?

EO: Tea. Cup of tea. I have my mother’s China, and I have my mother in law’s China. I have my grandmother’s in laws Chin. I think a little cup of tea and a little lace doily.

AS: I like it. Any favorite tea brands? I’m also a tea fan.

EO: I like Earl Grey, and I raspberry. Raspberry for most afternoons and Earl Grey. There is a very nice tea place up here that supplies a lot of teas. It’s called Harney & Son’s. They do some lovely teas for various teas and stately homes and libraries. So I’ll give them a plug too.

AS: Oh, that’s lovely. Well, just to kind of wrap up a little bit, could you remind us what’s next for you? Anything you can tease readers with?

EO: The first story is published in an anthology. and it’s a short story called Masthead. The second is coming out in October and something called the BOLD awards, which is bizarre, outlandish, limitless and daring, which is sort of goes right there with a cup of tea, right? So those are the two short stories I have out. The first full length novel, which does not involve the English dancing, is at my editors right now we don’t have a firm publication date. Fingers crossed fall or early 2022.

AS: All right, excellent. Just one more question. This is a pretty difficult one, I think. Who is your favorite character that you’ve created?

EO: Oh, probably Bern. He is the big bruiser who can country dance. I’m a little in love with him. Doyle is the AI program. He’s kind of a jerk all the time. But I think I’m a little in love with the big bruiser who can country dance. I like that one a lot. I’m probably most sympathetic to Mary Watson, the AI programmer who is a librarian. I mean, she’s probably the closest one to me, but her sort of boyfriend on and off, that’s the one I think I’m in love with right now.

AS: Thank you! We are so excited again to have met with you, and we are looking forward to seeing the short stories coming out in the future.

EO: Thank you for interviewing me and having me! This was a lot of fun.