A Short History of Horror

Horror fiction arose in the late eighteenth century with such works as Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, Matthew G. Lewis’s The Monk, and Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho. Frankenstein and Dracula followed in their wake over the next hundred or so years, but it took the invention of the movies to implant the images of horror even more deeply in our minds. Here’s a brief list of great moments of movie horror in more or less chronological order.

The silent period first exploited the movie magic of stop motion, double exposure, and other techniques to make the supernatural more tangible and the frisson of fear more intense. Two early classics are The Golem (1920), a Frankenstein-esque tale of the creature created to protect the Jews of Prague; The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), a wild tale of a sideshow hypnotist with a somnabulist assistant whom he sends off to murder; and Nosferatu (1922), F. W. Murnau’s unauthorized takeoff of Dracula, which introduced the disintegration in daylight motif.

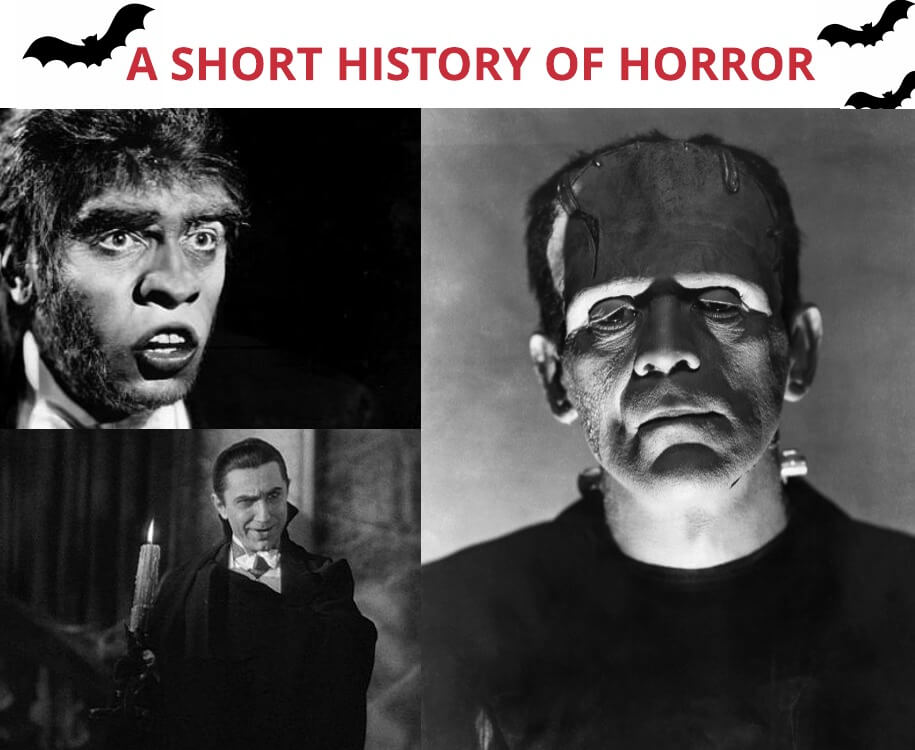

At the dawn of sound film in the early 1930s, Carl Laemmle Jr. took over Universal Studios from his father and produced several memorable pioneering films including James Whale’s Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Invisible Man. Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi became perennial horror stars. The only major horror film of the early 1930s not made by Universal was Paramount’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, starring Fredric March in the dual role. Directed by Rouben Mamoulian, it displayed a dazzling array of special effects, some derived from silent predecessors and some part of the new sound film arsenal. March won the Oscar for Best Actor, the first and last to win for a horror film until more than sixty years later when Anthony Hopkins won for Silence of the Lambs.

At the dawn of sound film in the early 1930s, Carl Laemmle Jr. took over Universal Studios from his father and produced several memorable pioneering films including James Whale’s Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Invisible Man. Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi became perennial horror stars. The only major horror film of the early 1930s not made by Universal was Paramount’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, starring Fredric March in the dual role. Directed by Rouben Mamoulian, it displayed a dazzling array of special effects, some derived from silent predecessors and some part of the new sound film arsenal. March won the Oscar for Best Actor, the first and last to win for a horror film until more than sixty years later when Anthony Hopkins won for Silence of the Lambs.

By the 1940s, the Universal monsters had been revived and recombined in so-called “rally” films such Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man and House of Dracula, as well as comic versions like Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. But the true creepy spirit of horror remained in the low-budget films produced by Val Lewton for RKO and directed by Jacques Tourneur, including Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie, which substituted dark shadows and psychological innuendo for monster makeup and special effects.

Horror in the 1950s intermingled with science fiction, as the monster often became easily identified in the Cold War with Communism in general and Russia in particular. The conservative film The Thing From Another World (1951) featured a blood-drinking alien who was only defeated when the scientists who wanted to study it were overruled by the army men who wanted to kill it. Whether the final caution “Watch the skies” referred to flying saucers or Soviet planes was left ambiguous. The conclusion of its liberal counterpart of the same year, The Day the Earth Stood Still, was that the human race needed to learn how to live in peace or be destroyed by the alien (who had a pleasant English accent) and his death-ray-dealing robot assistant, who turned out to be the real master.

The 1960s marked a change in many areas of the American movie business and in horror as well. Alfred Hitchcock kicked off the decade with Psycho, presenting a serial killer with a mother complex out of Freud with a sidebar of necrophilia. Then, in 1968, from Pittsburgh came George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. Like Hitchcock, Romero mixed the seemingly normal with the horrific in a story of reanimated dead who may have been affected by a radioactive space probe. Ten years later in Dawn of the Dead, the zombies have been resurrected by a mysterious virus or other phenomenon, and in their full-scale attack on a suburban shopping center resemble consumerism gone mad.

The satiric edge of Romero’s zombie films continued into the 1970s, along with returns to the original stories, now amped up with more blood and sex. These exhibited a strong influence from the British horror films made by Hammer Studios in the 1950s, as well as from a growing number of horror films from Spain, France, and Italy. But the ’70s also witnessed the first novels of Stephen King (Carrie, Salem’s Lot, The Shining), whose continuingly prolific interventions in all genres and subgenres of literary horror contributed immeasurably to its importance in American culture.

With all classic film genres up for grabs and revision in the New Hollywood of the 1970s, horror was no exception. From the religiously tinged horror of The Exorcist to the rural cannibalism of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre to the outer space terror of Alien, horror came out of its former B-movie status to fuel A-movie blockbusters. By the 1980s, the ’70s slasher franchise Halloween had paved the way for further slasher excursions such as Friday the 13th and the Nightmare on Elm Street series, with its innovative heroines who were no longer the passive victims of so many previous films. The respectability of horror films gained momentum as prestigious filmmakers dabbled in the genre: Steven Spielberg wrote the story for Poltergeist and Stanley Kubrick directed The Shining, while the young director Kathryn Bigelow came out with a tantalizing tale of nomadic vampires down on their luck in Near Dark.

Since then, horror films and horror fiction have become a permanent part of the worldwide cultural landscape. The fears raised and shaped by stories of horror seem especially suited to our own era of international tensions, populist paranoia, and mistrust of governmental institutions. Japanese horror, in particular, with its array of ghosts and poltergeists and its emphasis on psychological tension, has been a strong influence on American films. In recent years, while important films that advance horror traditions have come from such disparate countries as Sweden (Let the Right One In) and Iran (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night), American horror has often amped the blood and gore with the special effects of torture-porn films such as the Saw and Hostel series. But in whatever format, horror seems to be here to stay.